Prabowo, the Ghost of Soeharto, and Indonesia’s Reckoning with Its Past

The ghost of Suharto still haunts Indonesia, and perhaps no one is more entangled in that legacy than the current president, Prabowo Subianto.

Once married to Siti Hediati Hariyadi, a daughter of the late strongman Suharto, Prabowo’s links to the former regime are personal as well as political. His rise to the presidency in 2024 is a striking comeback for a man whose military career ended in disgrace during Indonesia’s democratic transition.

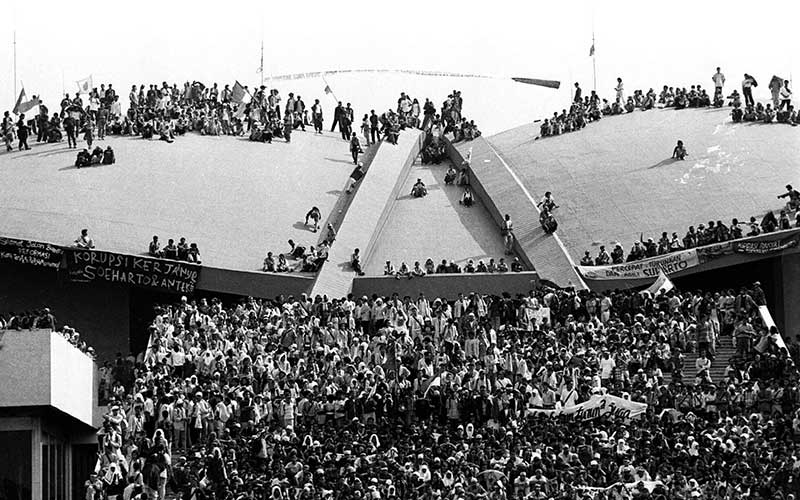

In the late 1990s, as Suharto fell, Prabowo was discharged from the military amid allegations of human rights abuses—in East Timor, and during the unrest and violence of May 1998. Shortly after, he went into self-imposed exile in Jordan. These allegations have never fully disappeared, casting a long and persistent shadow over his political ambitions.

Prabowo has consistently denied any wrongdoing, yet his past has been a major issue in every one of his presidential campaigns. At one point, he was banned from entering the United States over these allegations—a ban that was lifted years later by President Donald Trump.

Was He Guilty?

The truth remains elusive.

Indonesia has officially acknowledged human rights violations in East Timor, and several military figures have faced trial—but none have been convicted. Several members of the “Tim Mawar” unit, operating under Prabowo’s broader command, were tried and convicted for the kidnapping and torture of pro-democracy activists.

While Prabowo commanded troops in East Timor in the early 1980s, there is no public evidence directly tying him to specific atrocities. However, a military inquiry in the 1990s concluded that he had acted "beyond his authority" and violated the chain of command. The full findings were never released, and Prabowo was never criminally charged.

The 1998 Riots and Ethnic Tensions

The May 1998 riots—a dark chapter in Indonesia’s history—are often described in Chinese-language media as anti-Chinese pogroms, there have long been suspicions of military involvement. Was Prabowo directly involved? It’s unclear. Some accounts instead implicate then-Defense Minister Wiranto. Interim president B.J. Habibie ordered an investigation, but the report was never released.

Despite lingering doubts, there’s little evidence that Prabowo himself harbours sinophobic views. In fact, he has largely avoided race-based appeals, and he publicly supported Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (Ahok), a Christian Chinese-Indonesian, in his run for vice governor of Jakarta—something few major politicians dared to do.

From Pariah to President

Prabowo ran for president three times—2009, 2014, and 2019—before finally winning by a landslide in 2024. His campaign benefited from his image as a strongman with military credentials and a sense of stability in an increasingly polarized political environment. However, his controversial running mate, a young inexperienced figure, raised concerns about the future leadership of the country should Prabowo become incapacitated.

Compared to his rivals in the 2024 election—many of whom leaned heavily on sectarian and religious rhetoric, or lacked national recognition, Prabowo may have appeared the least divisive and most pragmatic option. For many voters, Prabowo appeared to represent continuity, order, and perhaps a cautious optimism.

His recent pro-China stance could offer reassurance to Chinese-Indonesians who have long feared being scapegoated or side-lined in national politics.

Still, the weight of his past is difficult to ignore. Unanswered questions, unpublished investigations, and the murky legacy of the Suharto era continue to shadow his presidency. As leader of a post-Reformasi Indonesia, Prabowo now faces the daunting challenge of reconciling the nation’s aspirations for justice and transparency with the ghosts of its past.

Let’s hope—for the country’s sake—that he rises to that challenge and stays healthy. The prospect of his inexperienced deputy taking over would be deeply concerning. Time will tell if he is the right man to lead. Let future historians be the judge.

Member discussion