Basic Text Processing Techniques

Introduction

In today’s digitally driven world, text data serves as a cornerstone of communication and information exchange, spanning domains such as social media, healthcare, finance, and academia. However, raw text whether in tweets, research papers, or customer reviews is inherently unstructured, containing inconsistencies in formatting, spelling, and grammar that hinder computational analysis. Text processing addresses this challenge by converting unstructured text into a standardized, machine-readable format. This transformation relies on foundational techniques like tokenization, normalization, and regular expression (regex)-based pattern matching, which collectively enable natural language processing (NLP) systems to interpret and analyse human language effectively.

Here we explore the core principles of text processing, focusing on its role in preparing textual data for computational tasks. Key methods to be examined include tokenization (segmenting text into words, sentences, or subwords), normalization (standardizing case, punctuation, and word forms), and regex (identifying and manipulating text patterns). Additionally, algorithms such as the Porter stemming algorithm and metrics like edit distance will be discussed to illustrate advanced normalization strategies. By understanding these techniques, readers will gain insight into how unstructured text is systematically transformed into structured data, forming the basis for applications like search engines, sentiment analysis, and machine translation.

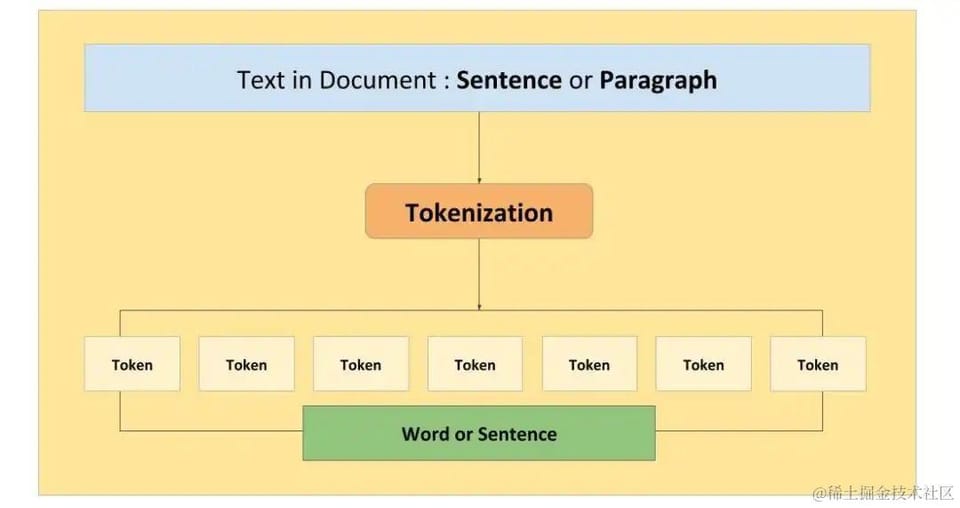

Tokenization: Segmenting Text into Meaningful Units

Tokenization is the foundational step in text processing, where raw text is divided into smaller, meaningful units called tokens. These tokens - such as words, sentences, or sub-words - serve as the basic elements for computational analysis. The process varies depending on the task, language, and domain, but its goal remains consistent: to convert unstructured text into structured, machine-interpretable data.

Word Tokenization

Word tokenization splits text into individual words or word-like units. For example, the sentence "Natural Language Processing (NLP) unlocks insights from text." might be tokenized into:

["Natural", "Language", "Processing", "(", "NLP", ")", "unlocks", "insights", "from", "text", "."]

Simple methods like whitespace splitting work for basic cases but struggle with contractions ("don’t") or hyphenated words ("state-of-the-art"). Regular expressions (regex) offer greater flexibility. In Python’s re module, a custom pattern can handle contractions and hyphens:

import re

text = "Don't over-tokenize state-of-the-art!"

tokens = re.findall(r"\w+(?:[-']\w+)*|[\W_]", text)

print(tokens) # Output: ["Don't", "over-tokenize", "state-of-the-art", "!"]

This regex pattern (\w+(?:[-']\w+)*) matches words with optional hyphens or apostrophes, preserving compounds like "state-of-the-art" as single tokens.

Sentence Tokenization

Sentence tokenization segments paragraphs into coherent sentences. Consider the text "Dr. Smith arrived at 5 p.m. The meeting began shortly after." A naïve split on periods would incorrectly break "5 p.m." and "Dr." into separate sentences. Libraries like NLTK’s sent_tokenize handle such cases using pre-trained models:

from nltk.tokenize import sent_tokenize

text = "Dr. Smith arrived at 5 p.m. The meeting began shortly after."

sentences = sent_tokenize(text)

print(sentences) # Output: ["Dr. Smith arrived at 5 p.m.", "The meeting began shortly after."]

The model recognizes "Dr." and "p.m." as abbreviations, ensuring proper segmentation.

Subword Tokenization

Subword tokenization breaks rare or compound words into smaller components. For instance, the word "unhappily" might split into ["un", "happy", "ly"]. Modern NLP models like BERT use algorithms such as WordPiece to achieve this:

from transformers import BertTokenizer

tokenizer = BertTokenizer.from_pretrained("bert-base-uncased")

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize("unhappily")

print(tokens) # Output: ["un", "##happy", "##ly"]

The ## prefix indicates subwords that should be merged with preceding tokens during decoding. This approach handles out-of-vocabulary words and reduces the size of the model’s vocabulary.

Challenges and Applications

Tokenization’s challenges include linguistic diversity (e.g., Chinese lacks spaces between words) and domain-specific text (e.g., scientific terms like "pH"). Despite these hurdles, tokenized text underpins critical NLP tasks. Search engines use tokens to index documents, sentiment analysis models evaluate tokens like "excellent" or "disappointing", and machine translation systems convert tokens between languages.

By balancing rule-based methods (regex) and statistical models (WordPiece), tokenization ensures both precision and flexibility. While seemingly simple, it is a critical first step in transforming raw text into actionable insights.

Normalization: Standardizing Text for Analysis

Normalization is a critical step in text processing that standardizes text into a consistent format, enabling algorithms to analyze it effectively. This process reduces noise and variability inherent in human language, ensuring that words with similar meanings are treated uniformly. Below, we explore key normalization techniques, their implementations, and considerations.

Case folding simplifies text by converting all characters to a single case, typically lowercase. This ensures that words like "Apple" and "apple" are treated as identical, which is particularly useful for search engines or text-matching tasks. For example:

text = "Natural Language Processing (NLP) unlocks Insights."

normalized_text = text.lower()

print(normalized_text) # Output: "natural language processing (nlp) unlocks insights."

While case folding improves consistency, it risks conflating distinct meanings. Proper nouns like "US" (United States) and the pronoun "us" become indistinguishable after lowercasing, which may harm tasks like named entity recognition.

Stop word removal filters out high-frequency words (e.g., "the," "and," "is") that contribute little to semantic analysis. Libraries like NLTK provide predefined stop word lists for various languages:

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

text = "To be or not to be, that is the question."

stop_words = set(stopwords.words("english"))

tokens = text.split()

filtered_tokens = [word for word in tokens if word.lower() not in stop_words]

print(filtered_tokens) # Output: ["To", "not", "question."]

This technique is valuable for tasks like topic modeling, where focus is on content-rich terms. However, over-removal can strip critical context, such as in the phrase "to be or not to be," where stop words are essential to the meaning.

Stemming, particularly via the Porter stemming algorithm, reduces words to their root form by stripping suffixes. This rule-based approach is fast but can produce non-linguistic roots. For example:

from nltk.stem import PorterStemmer

ps = PorterStemmer()

words = ["running", "flies", "happily", "universal"]

stems = [ps.stem(word) for word in words]

print(stems) # Output: ["run", "fli", "happili", "univers"]

While "running" correctly stems to "run," "flies" becomes "fli," and "universal" loses its meaning as "univers." Despite these limitations, stemming remains popular for its speed and simplicity in applications like search engines, where recall is prioritized over precision.

Edit distance, often measured using the Levenshtein distance, quantifies the minimum number of operations (insertions, deletions, substitutions) needed to transform one string into another. This metric is pivotal for spell checkers and fuzzy string matching:

def levenshtein_distance(s1, s2):

# Dynamic programming implementation

m, n = len(s1), len(s2)

dp = [[0]*(n+1) for _ in range(m+1)]

for i in range(m+1):

for j in range(n+1):

if i == 0:

dp[i][j] = j

elif j == 0:

dp[i][j] = i

else:

cost = 0 if s1[i-1] == s2[j-1] else 1

dp[i][j] = min(dp[i-1][j] + 1, # Deletion

dp[i][j-1] + 1, # Insertion

dp[i-1][j-1] + cost) # Substitution

return dp[m][n]

print(levenshtein_distance("kitten", "sitting")) # Output: 3

The distance between "kitten" and "sitting" is 3 (substitute "k" → "s," insert "i," insert "g"). While powerful, edit distance calculations are computationally expensive for large datasets, often requiring optimizations like thresholding or pre-filtering.

Trade-offs and Synergies

Normalization techniques must be applied judiciously. For instance:

- Case folding and stop word removal streamline text but risk losing context.

- Stemming sacrifices linguistic accuracy for computational efficiency, whereas lemmatization (not covered here) provides valid roots at the cost of speed.

- Edit distance enables robust error correction but struggles with semantic differences (e.g., "there" vs. "their").

In practice, these techniques are often combined. For example, a search engine might lowercase a query, remove stop words, stem remaining terms, and use edit distance to handle typos. By balancing these methods, normalization ensures that raw text is transformed into a structured, analysable form, ready for advanced NLP tasks like sentiment analysis or machine translation.

Regex and Corpora: Tools and Data for Text Processing

Regular expressions (regex) and corpora are indispensable components of text processing, offering the tools and datasets needed to transform unstructured text into structured, analysable information. Regex provides a flexible syntax for pattern-based text manipulation, while corpora serve as the raw material—text collections—that fuel NLP tasks. Together, they enable tasks ranging from data cleaning to model training.

Regex is a domain-specific language for defining search patterns in text. Its strength lies in precision and adaptability, making it ideal for tasks like extracting structured data or removing noise. For instance, cleaning a tweet by stripping URLs and hashtags can be achieved with a few lines of Python:

import re

tweet = "Check out #NLP! Visit https://example.com 😊"

clean_tweet = re.sub(r"https?://\S+|#\w+", "", tweet) # Remove URLs and hashtags

print(clean_tweet) # Output: "Check out ! Visit 😊"

Here, the regex pattern https?://\S+ matches HTTP/HTTPS URLs, while #\w+ targets hashtags. Regex also powers entity extraction, such as identifying email addresses:

text = "Contact: [email protected] or [email protected]"

emails = re.findall(r"[\w\.-]+@[\w\.-]+", text)

print(emails) # Output: ["[email protected]", "[email protected]"]

However, regex struggles with nested or context-dependent patterns. For example, parsing HTML tags with regex often fails due to nested structures, necessitating specialized parsers like BeautifulSoup.

Corpora are structured collections of text used to train models, benchmark algorithms, or study linguistic phenomena. Examples include general-purpose corpora like the Brown Corpus (categorized English texts) and domain-specific collections like PubMed abstracts (biomedical research). Preprocessing a corpus often involves encoding detection, boilerplate removal, and normalization. For example, cleaning a web-scraped corpus might require regex to strip HTML tags:

html_text = "<p>Hello <b>World</b>!</p>"

clean_text = re.sub(r"<[^>]+>", "", html_text) # Remove HTML tags

print(clean_text) # Output: "Hello World!"

Corpora quality directly impacts downstream tasks. A medical corpus skewed toward one disease may bias diagnostic models, while a social media corpus with diverse slang ensures robustness in sentiment analysis.

Synergy Between Regex and Corpora

Regex and corpora often work in tandem. For instance:

- Corpus Annotation: Regex labels entities (e.g., dates, locations) in legal documents.

- Data Filtering: Extract domain-specific terms (e.g., gene names like BRCA1) from biomedical texts.

- Quality Control: Identify spam or gibberish in a web corpus using patterns like excessive punctuation (

!!!).

A practical example is hashtag extraction from social media corpora:

tweets = ["Loving #NLP!", "Check out #MachineLearning!"]

hashtags = [re.findall(r"#(\w+)", tweet) for tweet in tweets]

print(hashtags) # Output: [["NLP"], ["MachineLearning"]]

This regex pattern #(\w+) captures hashtags while ignoring symbols, enabling trend analysis.

Challenges

- Regex Complexity: Crafting patterns for multilingual or evolving text (e.g., emojis like 🤖) demands constant updates.

- Corpus Bias: Models trained on historical news corpora may inherit outdated gender or cultural biases.

- Scalability: Processing terabyte-scale corpora (e.g., Common Crawl) requires optimized regex and distributed computing.

Applications

- Search Engines: Regex filters queries (e.g.,

filetype:pdf), while corpora index documents. - Spam Detection: Regex flags suspicious patterns (

"FREE!!!"), validated against email corpora. - Lexicography: Building dictionaries by extracting terms from literary corpora using regex.

Applications of Text Processing Techniques

Text processing techniques power a wide array of real-world applications, transforming unstructured text into actionable insights across industries. Below, we explore key use cases, supported by code snippets and examples, to illustrate how these methods drive modern NLP systems.

1. Search Engines

Search engines rely on tokenization, normalization, and regex to index and retrieve documents efficiently. For instance:

Regex filters advanced search patterns (e.g., filetype:pdf):

import re

text = "Search filetype:pdf 'machine learning' site:example.com"

file_type = re.search(r"filetype:(\w+)", text).group(1) # "pdf"

Stemming ensures queries like "running shoes" match documents containing "ran" or "runs":

from nltk.stem import PorterStemmer

ps = PorterStemmer()

query = "running shoes"

stemmed_query = [ps.stem(word) for word in query.split()] # ["run", "shoe"]

2. Sentiment Analysis

Normalization and stop word removal help models focus on sentiment-bearing terms. For example:

Case Folding and Stemming:

normalized_words = [ps.stem(word.lower()) for word in filtered_words]

# ["movi", "terribl", "bore", "visu", "stun."]

Stop Word Removal:

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

text = "The movie was terribly boring but visually stunning."

filtered_words = [word for word in text.split() if word not in stopwords.words("english")]

# Output: ["movie", "terribly", "boring", "visually", "stunning."]

These steps simplify text for classifiers to detect sentiments like "boring" or "stunning."

3. Machine Translation

Subword tokenization handles rare words and morphological variations across languages:

from transformers import BertTokenizer

tokenizer = BertTokenizer.from_pretrained("bert-base-multilingual-cased")

text = "La communication est essentielle." # French for "Communication is essential."

tokens = tokenizer.tokenize(text) # ["La", "com", "##mun", "##ication", "est", "essentielle", "."]

By breaking words into subunits, models like BERT translate complex terms effectively.

4. Spam Detection

Regex and edit distance identify malicious content:

Edit Distance corrects typos in user reports:

def correct_spelling(word, dictionary):

suggestions = [w for w in dictionary if levenshtein_distance(word, w) <= 2]

return min(suggestions, key=lambda x: levenshtein_distance(word, x)) if suggestions else word

print(correct_spelling("recieve", {"receive", "relieve"})) # "receive"

Regex Patterns flag phishing attempts:

email = "CLAIM YOUR PRIZE $$$ TODAY! Click http://malicious.link"

is_spam = re.search(r"\b(?:WIN|PRIZE|£{3,})\b|http://\S+", email) # Returns True

5. Data Mining

Regex extracts structured data (e.g., dates, phone numbers) from unstructured text:

text = "Meeting on 25/12/2023. Call +1-555-123-4567."

dates = re.findall(r"\b\d{2}/\d{2}/\d{4}\b", text) # ["25/12/2023"]

phones = re.findall(r"\+\d{1,3}-\d{3}-\d{3}-\d{4}", text) # ["+1-555-123-4567"]

Normalization aggregates variants like "Data" and "data" for trend analysis.

6. Chatbots and Virtual Assistants

Tokenization and normalization enable intent recognition:

user_input = "Book a flight to NEW YORK on 10th May."

tokens = user_input.lower().split() # ["book", "a", "flight", "to", "new", "york", ...]

destination = " ".join(tokens[4:6]) # "new york"

Systems like Siri or Alexa use such pipelines to parse requests accurately.

Challenges in Text Processing

Text processing, while foundational to NLP, faces significant challenges stemming from linguistic complexity, computational limitations, and evolving language use. Below, we explore these hurdles, supported by examples and code snippets, to illustrate the practical and theoretical obstacles practitioners encounter.

1. Linguistic Diversity

Human languages vary drastically in structure, morphology, and script, complicating universal text processing pipelines.

Agglutinative Languages: Turkish or Finnish form long compound words that challenge stemming:

# Turkish example: "çekoslovakyalılaştıramadıklarımızdanmışsınız" (You are among those we couldn't Czechoslovakianize)

from snowballstemmer import TurkishStemmer

stemmer = TurkishStemmer()

stem = stemmer.stemWord("çekoslovakyalılaştıramadıklarımızdanmışsınız") # Output: "çekoslovakyalılaştıramadık"

Even advanced stemmers may fail to split or reduce such terms meaningfully.

Non-Latin Scripts: Languages like Arabic or Mandarin lack spaces between words, requiring specialized tokenizers.

# Chinese tokenization with Jieba

import jieba

text = "自然语言处理很重要" # "Natural language processing is important"

tokens = jieba.lcut(text) # Output: ["自然语言", "处理", "很", "重要"]

Without language-specific tools, tokenization fails to capture meaningful units.

2. Over-Normalization

Aggressive normalization can strip critical semantic or syntactic information.

Case Folding Pitfalls: Lowercasing erases distinctions between entities.

text = "Apple released M1. Did apple sales grow?"

normalized = text.lower() # "apple released m1. did apple sales grow?"

Here, "Apple" (company) and "apple" (fruit) become indistinguishable.

Stemming Errors: The Porter algorithm often produces non-linguistic roots.

from nltk.stem import PorterStemmer

ps = PorterStemmer()

print(ps.stem("university")) # Output: "univers"

Over-stemming renders "university" unrecognizable, harming downstream tasks like search.

3. Computational Costs

Scalability issues arise with large datasets or complex operations.

Regex Complexity: Nested patterns (e.g., parsing HTML) become computationally expensive.

# Inefficient HTML parsing with regex

html = "<div><p>Hello <b>World</b></p></div>"

re.findall(r"<([a-z]+)>(.*?)</\1>", html) # Fails on nested tags

Edit Distance Calculations: Levenshtein distance has a time complexity of O(nm), making it impractical for large-scale data.

# Slow for long strings or large datasets

levenshtein_distance("abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz", "abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxzy") # 26-character comparison

Optimizations like python-Levenshtein or thresholding are often required.

4. Corpus Bias

Training or analysis on skewed corpora perpetuates biases.

Domain Bias: A medical corpus focused on cancer may underrepresent rare diseases.

Cultural Bias: Historical corpora often reflect outdated gender or racial stereotypes.

# Biased word embeddings trained on old news corpora

# "doctor" might associate more with "he," "nurse" with "she"

Mitigating bias requires deliberate curation and debiasing techniques.

5. Evolving Language

Language constantly adapts, challenging static rules and models.

Slang and Neologisms: Terms like "rizz" (charisma) or "ghosting" (ignoring messages) emerge rapidly.

Emojis and New Formats: Emojis (😂) or Markdown syntax (**bold**) require updated processing.

# Regex to remove emojis (may need constant updates)

text = "Text processing is 🔥! 😊"

cleaned = re.sub(r"\U0001F600-\U0001F64F", "", text) # Removes 😊 but not 🔥

6. Context Sensitivity

Many techniques ignore context, leading to errors.

Stop Word Removal: Critical phrases like "to be or not to be" lose meaning when stop words are stripped.

Homographs: Words like "lead" (metal) vs. "lead" (guide) require disambiguation.

# Lemmatization without context fails

from nltk.stem import WordNetLemmatizer

lemmatizer = WordNetLemmatizer()

print(lemmatizer.lemmatize("banks", pos="n")) # "bank" (correct)

print(lemmatizer.lemmatize("banks", pos="v")) # "bank" (incorrect for "river banks")

Conclusion

Text processing techniques - tokenization, normalization, regular expressions, and corpus management- serve as the bedrock of natural language processing (NLP), enabling machines to transform unstructured text into actionable insights. By segmenting text into tokens, standardizing its form, and leveraging pattern-based rules, these methods empower applications ranging from sentiment analysis and search engines to machine translation and chatbots. For example, the Porter stemming algorithm simplifies words like "running" to "run," while regex patterns extract structured data such as emails or dates from chaotic text. These foundational steps ensure that raw language data becomes interpretable for computational models.

However, the journey from raw text to structured data is fraught with challenges. Linguistic diversity complicates universal solutions, as agglutinative languages like Turkish demand advanced tokenizers, and non-Latin scripts like Arabic require specialized handling. Over-normalization risks stripping semantic meaning, as seen when "university" is reduced to "univers" by aggressive stemming. Computational bottlenecks, such as the high cost of edit distance calculations for large datasets, further strain resources. Corpus bias, whether cultural or domain-specific, can propagate inequities in NLP systems, while evolving language forms - slang, emojis, or new dialects - demand constant adaptation of static rules.

Future Outlook

The future of text processing lies in hybrid frameworks that marry rule-based techniques with neural and statistical approaches. Innovations in three key areas are poised to redefine the field:

- Context-Aware Models:

Transformer architectures like BERT and GPT-4 already integrate subword tokenization (e.g., WordPiece) with contextual embeddings, enabling nuanced understanding of polysemous words like "bank" (financial institution vs. river edge). Future models may automate normalization steps, reducing reliance on manual rules. - Multilingual and Low-Resource Support:

Advances in zero-shot learning and massively multilingual corpora will democratize NLP for underrepresented languages. For instance, tools like Google’s Universal Sentence Encoder aim to map diverse languages into a shared semantic space, enabling cross-lingual applications without extensive labeled data. - Ethical and Efficient Processing:

Techniques for bias detection (e.g., fairness-aware algorithms) and energy-efficient tokenization will address ethical and environmental concerns. Sparse attention mechanisms in models like Longformer reduce computational overhead, making large-scale text processing sustainable. - Adaptive Tools for Evolving Language:

Real-time adaptation to linguistic shifts—such as detecting emerging slang or emojis—will rely on dynamic regex-like patterns powered by reinforcement learning. For example, a system could auto-update its tokenizer to parse new hashtag trends (e.g., #AIethics) without human intervention.

Final Thoughts

Text processing is not a static discipline but an evolving practice that mirrors the dynamism of human language itself. While traditional techniques like regex and stemming remain indispensable, their integration with neural models and ethical frameworks will drive the next generation of NLP systems. As we navigate this evolution, the focus must expand beyond technical prowess to include inclusivity, sustainability, and adaptability. By doing so, text processing will continue to unlock the transformative potential of language data, bridging the gap between human communication and machine intelligence in an increasingly interconnected world.

Member discussion